As a child and teenager, I simply accepted that there were different rules for me than my male peers. There were certain precautions that I was taught that my male peers never had to learn, the most notable of which was when the girls were separated out my sophomore year of high school and taught self-defense for three weeks while the boys got to play basketball. It didn’t even occur to me to question the injustice of that. I was sixteen, growing up in probably the safest part of the Bay Area, and I remember walking alone to the local Blockbuster one night. It was barely after 7 PM, less than five blocks from my house in a middle-class residential neighborhood. A young woman on the street going in the opposite direction passed me and she said, “Be careful, watch behind you,” and I realized a man had been following me. I was scared, of course. I hid out in the Blockbuster until I was sure he was gone, but I also internalized it as a mere inconvenience. This man who had decided to stalk me, a nominal child, down a small suburban block struck me as mundane and commonplace as the Blockbuster being out of the latest new release. It has only been in recent years, well into my adulthood that I began to question the assumptions that fell behind this passive acceptance.

This, to lesser or greater degree, is the experience of women everywhere. These frameworks are so intrinsic that my experience is hardly unique. We have this tendency to think of populations living in fear on the other side of the world, victim to tyrannical regimes and extreme poverty. But the female population in every single country surveyed by Gallup lives in significantly greater fear than the male population. Globally, 62% of women feel unsafe as compared to 72% of men, a disparity of 10%. The gap is greater in high income countries, increasing to a 23% difference. Nowhere is this more exemplified than New Zealand, one of the safest places in the world. 85% of the male population feels safe walking alone in their own neighborhood at night, but only 50% of the women do--a gap of 35%, the largest disparity of all countries surveyed. Meanwhile the same percentage of women are fearful in their own neighborhoods in France as they are in Malawi (51%), but 78% of men in France feel safe where only 56% of men in Malawi do. Malawi is one of the world’s poorest countries and France falls within the top 25 richest. It doesn’t take much to draw the conclusion that greater prosperity translates to a larger benefit for men than women.

There are only seven countries that haven’t ratified or at least signed CEDAW, a treaty adopted by the UN in 1979 aimed at ending all discrimination against women: Tonga, Palau, Sudan, South Sudan, Iran, and Somalia (there are more who have signed but not acceded to it).But even as countries have made commitments to end discrimination against women, governments have shown only incremental, stumbling progress. 3.4 billion people on this planet will likely perceive themselves under threat of violence solely on the basis of their gender at some point in their lives. Somehow we’ve been content to confront the issue in name only. Why is it this way? How is it this way? How do we stop it? As it currently stands, there is many a 16-year-old girl who has blithely accepted that she can’t go running at night, or ride public transportation alone when it gets late, or leave her drink unattended at a party. Misogyny is so ingrained and pervasive that we very nearly see it as natural.

In her HuffPo article, solo female traveller Laurita Gorman says the following: “People are naturally curious about my travel plans and often ask where I am headed next. But when I share the name of the next country I’m headed, I am often flooded with an overreaction and some fear mongering dialogue and then pleaded with to cancel my plans.” We have a tendency to assume that the slavering barbarian hordes in other presumably uncivilized nations are grossly mistreating women to a greater degree, thus deflecting our own culpability. It is unavoidably true that there are cultures where women labor under deep oppression and violence, but nevertheless we can’t forget or ignore that there is significant work to be done in the so-called “first world.” That the messaging about fear, while perhaps warranted, may serve to reinforce old hegemonies rather than confront them.

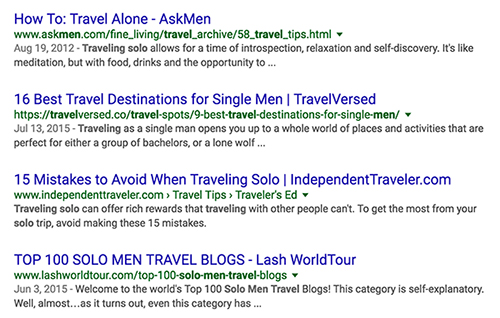

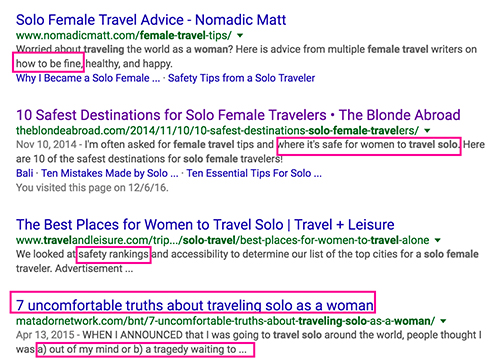

When I undertook this project, Travelfemme, it was because if I searched “male solo traveler” I got results regarding the best places to eat, drink, and have fun, whereas “female solo traveler” garnered a deluge of safety tips and warnings.

(The first few search results when you search solo male travelers)

I have been told personally to avoid certain countries, or been told that with regime changes, some places like Egypt or Turkey were no longer entirely hospitable to women. A woman I interviewed for the project who is a frequent traveller said that she hated the pervasiveness of what she termed “womens [sic] safety language,” and that she believes it “reinforces a toxic narrative that women are weak,” but at the same time she acknowledged that when traveling she was nevertheless wary, leaving a hotel bar one time in Belgium after a man bought her a drink and brought it to her because she couldn’t be sure if he’d interfered with it.

(Contrast that to the first few search results for solo female traveler)

Her anecdote was an example of the way that women’s safety is in itself a form of indoctrination. She had no reason to suspect that he’d done anything with it at all, but she’d known that she hadn’t seen the drink being made, and she’d grown up like many women in the United States born in the late 80s, taught through a variety of strident school programs and parental instructions never to leave her drink alone. Thus the drink itself rendered her unsafe and she felt she had to cut her night short. Obviously we can’t know whether or not the man had good intentions, but there are too many of us who have horror stories, so we move forward, continuing to keep a close hand on our drinks and monitoring people who pay attention to us.

When I began researching and designing the informational framework for the Travelfemme website what became clear is that no travel destination in the top 100 based on number of total visitors merited above a low B. Not even a single destination in the top ten. (The top ten travel destinations are as follows: Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, London, Macau, Kuala Lumpur, Shenzen, New York City, Antalya, and Paris for context). Thus travelfemme is not to highlight the horror stories, although these exist, but to assert the way that there is significant work to be done to enact gender parity, and that no country is exempt. It is a critical design piece meant to address the way wealthy popular destinations, some so-called idyllic paradises, do not regard their female citizens as equal.

There are many forums on which we need to get better--sexual and physical violence against women--but also the more shadowy arenas of sexual health and the limits on reproductive rights. The UN defines six different categories under which abortion may be legal: to save a woman’s life, to preserve a woman’s physical health, to preserve a woman’s mental health, in cases of rape or incest, in cases of fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or upon request. Only 61 countries have legalized it for all seven categories, and the United States is one. The UK is not. This is important for two reasons, because long term travellers may have to confront getting an abortion, but also because an ignored reality is that women are often forced to travel in order to obtain one. In which case, are there places for you? The de facto situation of women seeking abortions in the US is not without impediment, and many women even have to travel within the United States to find one. Many places make it appreciably difficult to receive emergency contraceptives. In the places where they are available, information is not well-disseminated. Additionally, most women menstruate, but even the most developed countries can make it hard for women to obtain a variety of cheap options, and the host of other places that continue to mark it an extreme stigma are also rampant. According to Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, “managing menstruation can be a debilitating, even deadly, problem – fueled by a combination of poverty, misinformation, stigma and superstition. One in ten girls in Africa misses school for the duration of her period each month. In Bangladesh, infections caused from filthy, contaminated rags are rampant. Menstrual hygiene has been linked to high rates of cervical cancer in India.”

In order to fight the far-reaching normalization of violence and discrimination against women, we need to begin acknowledging the ways that these things are significant concerns in women’s daily life. Why is it that feminine hygiene products, which are as essential to women as toilet paper, are not freely available in all bathrooms? Why is emergency contraception not available over the counter in many places when the far more dangerous DXM-laced cough syrup is? Why is it that we place so much stress on women using hormonal birth control when an idea for the male pill has been around since 1957, “and countless proposals have emerged in the decades since, but none of them has come to fruition. The science is there, and so are the potential users – and yet the industry continues to drag its feet.” When it comes to violence, we especially cannot address these issues by continuing to teach women to live in fear. In Nairobi, after they introduced a program that stresses “positive masculinity for the boys, positive empowerment, and...the prevention of rape and standing up for the rights of women” they noticed that boy’s started successfully intervening when witnessing sexual or physical violence and that rape dropped by as much as 20%. By 2017, every secondary school child in Nairobi is expected to undergo the program. Symptomatic treatment of the problems women face do not work, it’s time to look for something different.